One of the things Odissi has given me is a curiosity about hair. Mainly because it has changed the way I have been culturally conditioned to view it.

Let’s start with the irony: My attitude towards my hair is that of a person born into extreme privilege. I’m pathologically guilty of how easily it comes to me. Weary of knowing how fortunate I am. Hairdressers can’t really go wrong with my hair. There are no bad haircuts. There are no bad hair days. There are no moods. My hair is like the evergreen, immortal, never-changing houseplant of your dreams.

The funny thing is that I’m not very proud of my hair, because I’m painfully aware of how none of this has been earned; merely inherited rather. My hair is a shining emblem of my parent’s marriage — two diametrically opposite people's traits coming together as one — shiny, soft, silky meeting jet black, thick, and lush.

Perhaps that’s why I have never been able to view my hair as just that: hair. At some point in my youth - I wonder why - I began looking at my hair as a metaphor. It was all people could talk about when they saw me; I felt an overwhelming sense of how it defined me.

The OG shampoo ad hair girl. Dabur Amla kaale, ghane, lambe baal wali. Clinic Plus swish, swish hair wali. “Halo girl,” my sister calls me to date, after the first cool shampoo ad we ever saw on cable tv. “Rimi ke baal gudiya jaise hain, idhar karo toh idhar ho jaate hain, udhar karo toh udhar,” my aunt always said in glee while combing my hair, making her daughter jealous and me disappointed, during the summer vacation stays at my favourite cousin’s house.

I hated being a gudiya. What others saw as perfection, I perceived as conformity. What others gazed at with envy, I received as a limitation. A symbol of my seedhi-saadhi personality, my needle-straight hair. Malleable. Fawning. People-pleasing. Boring. Unchanging.

I felt parched for people’s attention for the rest of me. I never felt seen enough. ‘Good-girl hair’ is what I had, and that was exactly who I didn’t want to be. All my childhood had been spent in trying to be that, with no favourable results. Good girl ho ke dekh toh liya, is mein kya rakha hai? I scoffed.

Some time in my late teens, I began carefully observing heroines' hair in Bollywood movies. The ones that had the kaale, ghane, lambe baal were all repulsively monochromatic. Pious, fragile, rule-following, always in need of saving by the hero. Much later, I began noticing that the heroines who were a bit hatt ke had different hair. Kinks in their hair, and in their personality. Sridevi’s fun alter ego in Chalbaaz. Preiti Zinta in Dil Chahta Hai. Genelia in Jaane Tu Ya Jaane Na.

Curly, non-black hair came to mean a kind of person I wanted to be: spontaneous, wayward, fun, untameable. Moody and multitudinous. With the studiousness of a method actor, I set about becoming this person from the outside in: I permed my hair multiple times, sliced a shock of red into short hair once, then burgundy, mahogany, blonde. I failed to achieve the metaphor every time, outdone by my hair that grew out too fast, leaving me the same classic I was born as.

****

When I began dancing Odissi, I was curious to notice that the quality of a nayika’s (heroine’s) hair doesn’t matter as much as how she enjoys it. Hair is not just metaphor, it is gesture. It’s a thing that evokes emotion and expresses it too.

It is a quirk that reminds you of that one favourite person: One of the sweet and popular ways to remember young cowherd Krishna is the baby hair curlicues around his forehead (“peach fuzz” that so many women are trying to slick back in the Instagram reels section of my phone these days).

Hair is a riddle that makes you curious about someone a little outside the sphere of your understanding: One of the sexiest things about Shiva, is the man-bun of dreadlocks on his head, which a dancer shows in the exact way that it is tied - hands and fingers scraping up the locks and twisting them into a knot. Hair has an is-ness of strange unknowable universal phenomena: The way to show his “opposites attract” partner Parvati, is her elaborate, many-winged hair bun, from which she hangs beautiful jewels.

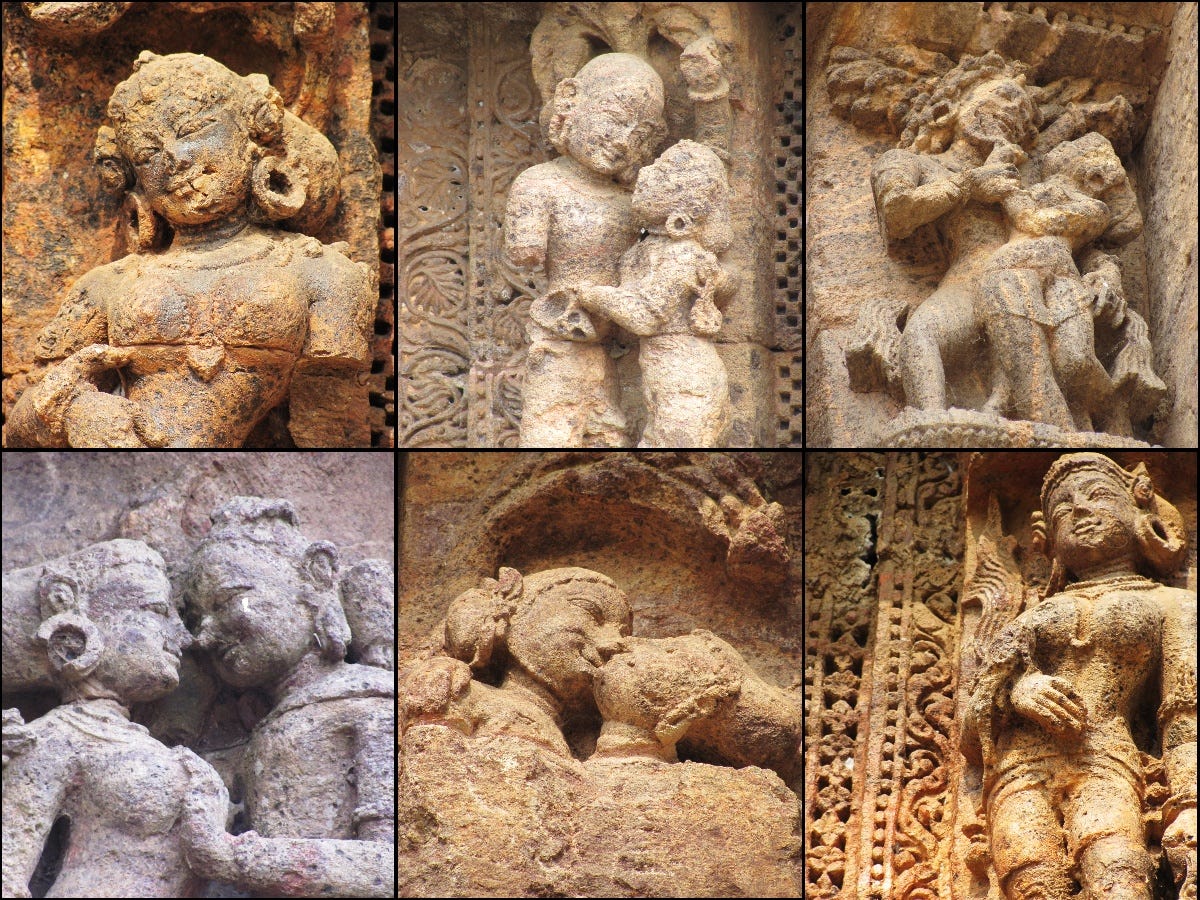

While spending time with the 12th century temple sculptures of Odisha, from which the style I learn takes its greatest inspiration, I noticed that none of the heroes and heroines are defined by pat metaphors of straight = good/ curly = funky/ black = superior. Truly timeless art has no space for such boring, rigid, neat metaphors that do not know how to play.

Here, in the iconography of gods and humans, I found riddles and games, with no set answers. Here, everything was valid, depending on the moment we were experiencing. Hair is your character, for enjoying and loving and shaping into what you are feeling. Durga won’t be judged for leaving her hair snake-like and uncombed; Shiva the ascetic doesn’t bother changing his hair when he gets a Sadashiv makeover and heads to his big fat royal wedding. Nayikas turn hair-tying gestures into dance poses, and the nayaks who sport bald, ragamuffin, or dandy hairdo-s get an equal amount of temple-wall-space. Hair is who you are, hair is not who you are perceived to be.

As a dancer onstage, I realised, my hair-identity doesn’t matter. Everything is wrapped up under my aharya of a moon-shaped crown and a flag-like taiya that makes me feel like a temple. None of it gets in the way of what I want to say and how I want to be seen. Many people think of the classical dance costume as a uniform or a code that objectifies the person dancing, but I found in it, the opposite: I was freed of the body I have always lived in, and the aesthetics that have always defined it. In the costume, I feel I am whittled down to my essence; this non-Swaati knows how to express the Swaati I truly am.

*****

Sometimes, being outside of yourself for a while gives you the courage to accept who you are within. I return to myself in a new way every time I remove my Odissi gear. Accepting and loving my hair has been a long journey. I have allowed its metaphor to extend in all directions.

I know that my hair has always been a means for me to get the attention of the people who couldn’t give it to me: my parents. My mother and I had so many meltdowns on school mornings – her raging and me bawling – because I wanted her to abandon all her neverending chores and the race-against-time, to comb my hair into elaborate plaits. French plaits still evoke long sighs in me; it is still some sort of a fantasy of mother-daughter love in my head.

The rare moments when I got my father’s full and undivided attention — that I wanted so badly as a child — was on the occasional Sunday he chose to give me an insane head massage with a bucketload of oil. There was nothing pleasurable about it in the usual sense. It was more like a tabla performance on my head (my father had been an amateur player in his youth) that left my hair more tangled than a skein of wool discovered by a cat. Then he’d take a wide-toothed comb and begin the arduous process of yanking it down to slick, detangled conformity. Then came my favourite part: the bizarre hairstyles he would create with my perfect hair. Ponytails emerging from ponytails. Half-eaten buns and weird plaits, hair sculptures all. If I tried to complain, he’d fool me by saying, “Arre, Russia mein sab girls ke aise hi hairstyle hote hain”. (Papa had just returned from a long official trip to Russia in the 80s, at the peak of Indo-Soviet love affair, and there was no compliment higher than that with a Russian context in my father’s eyes.) I succumbed, especially if he also threw in a “you have a swan neck, you should always tie your hair high up” along with it. My papa thinks I’m a swan, what more could little Swaati smile silently and endlessly about?

These head massages, however, were few and far between. For a very big part of my childhood, my father performed elaborate disappearing acts in the evenings and on weekends. Then I was suddenly a teenager and too cool for oily Sunday displays of affection.

I never did stop craving, however, for a man’s fingers in my hair. I dreamt of boyfriends who would show affection by combing my hair. (I never did learn to express this uncool desire, and so, no man ever dreamt of giving it to me). Sometimes instead of longing for it, I took matters into my own hands (a lifelong problematic habit, it seems), and let myself be the boyfriend — while dancing an Odissi abhinaya depicting Krishna styling Radha’s hair after a night of passionate, hair-toussling lovemaking.

The only time I ever get close to wish-fulfillment is, ironically, in the hairdresser’s chair. When a big, firm, masculine hand fluffs up the hair on the crown of my head with certitude, then slides down the length, right to the ends. Releasing all the wavy desire that lies pulsing under my head full of unproblematic, idyllic, unrippled hair. I surrender, and let myself be admired for what is – inherited or not - unquestionably mine.

In the last few years, one of the things I have begun as a self-care ritual is giving myself a head massage every week. I steal ten minutes between hectic school tiffin-packing mornings and standing right there in the kitchen, give my head a vigorous shake-up, then a gentle pat down. It’s both, a ritual and a reward. I’m a pathologically good girl, I know now, and for the first time in my life, I feel, that’s not such a bad thing.

(This is the fourth in a series I’m writing about my body, in continuation with the essay on breasts that I wrote for Immortal For a Moment by Natasha Badhwar (you can read the second about feet and third one about hands here). The essays from this series explore the crossroads between dance, culture and memory — which is my favourite place to rest, and which was the point of this substack after all.

This essay is adapted from an essay I wrote as a response to a prompt about hair, given to my beloved writers’ group Bavaal Writers Salon, by the brilliant Farjad Nabi. )

Swaati that is ingenious writing. So straight from the heart that I am sure it leaves most of your readers thinking about their body, with a new perspective 🙏

Swaati! Swaati, you are a magician! If I had to highlight what I loved, I would have to copy the whole post here. But this bit is pure gold - “Many people think of the classical dance costume as a uniform or a code that objectifies the person dancing, but I found in it, the opposite: I was freed of the body I have always lived in, and the aesthetics that have always defined it. In the costume, I feel I am whittled down to my essence; this non-Swaati knows how to express the Swaati I truly am.”

As always, you have brought your loving, direct gaze to a body part and described it in such detail that I am thinking anew of my relationship with my hair. I have only now in the recent past learned to love it for what it is - a curly, hell-raising, moody mess. Thank you for this post ❤️